Subxiphoid single-port thymectomy procedure: tips and pitfalls

Introduction

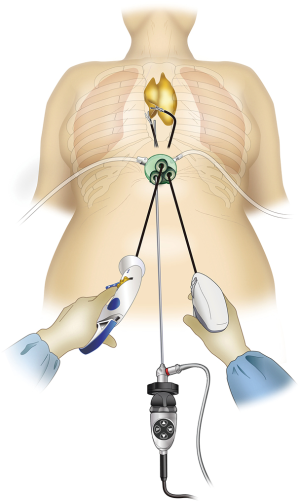

Endoscopic surgery rather than conventional median sternotomy is becoming the preferred thymectomy procedure for anterior mediastinal tumors and myasthenia gravis. Endoscopic approaches include transcervical thymectomy (1), unilateral or bilateral intercostal approach (2,3), and subxiphoid approach (4). The lateral intercostal approach is most frequently used and has esthetic advantages because the incision is made in the lateral chest wall. However, its shortcomings include difficulties in identifying the superior poles of the thymus and the contralateral phrenic nerve. Intercostal nerve damage occurs in all surgeries, with approximately 10% of patients developing post-thoracotomy pain syndrome and lifelong persistent pain and numbness (5). We previously described a subxiphoid single-port thymectomy procedure with CO2 insufflation of the mediastinum and removal of the thymus via a single incision below the xiphoid process in 2012 (4). The field of view offered by the camera scope inserted at the midline of the body below the xiphoid process facilitates locating the structures in the neck and bilateral phrenic nerves (Figure 1). Intercostal nerve damage is avoided because this approach does not enter the intercostal space, postoperative pain is minimal, and the results are esthetically excellent. Shortcomings of this approach include surgical manipulations unique to single-port surgery that require familiarity with the procedure. Subxiphoid single-port thymectomy is the most minimally invasive of the available approaches. This report describes an endoscopic subxiphoid, single-port thymectomy procedure, with tips to ensure success and pitfalls to avoid.

Operative techniques

Anesthesia

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia. Peripheral infusion is initiated in the right hand or foot to allow clamping of the innominate vein if it is injured. Differential lung ventilation is not required because lung expansion is suppressed by CO2 insufflation. In cases wherein concurrent pulmonary resection is required owing to the tumor having invaded one lung, partial resection of the lung is required, and/or the tumor is located toward the side, making it difficult to observe the phrenic nerve, deflation of the lungs facilitates surgical manipulations. In such cases, a double-lumen endotracheal tube is used for one-lung ventilation. The use of minimum pressure-controlled ventilation without positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) is recommended for patient ventilation. Using PEEP, the lungs are excessively inflated and can impede the field of view. Elevated blood CO2 can be managed by increasing the ventilation frequency.

Instrumentation and patient position

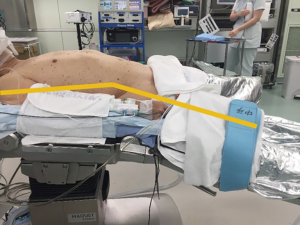

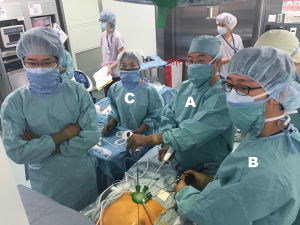

The patient is placed in the supine position with the legs apart. The operating table is tilted so that the cranial and caudal sides are lower than the epigastric fossa where the xiphoid process is located, and the abdomen protrudes upward. This position makes it easier for the surgeon to reach the rear surface of the sternum with the tip of the forceps when separating the thymus from the rear surface of the sternum (Figure 2). The surgeon stands between the patient’s legs, the assistant stands to the right of the patient to manipulate the camera scope, and the scrub nurse stands to the left of the patient (Figure 3).

Subxiphoid single-port thymectomy

A vertical or horizontal incision of approximately 3 cm is made 1 cm caudal to the xiphoid process. Vertical incisions can be easily extended in the caudal direction to remove a large tumor. Horizontal incisions result in less conspicuous postoperative wounds because they run along Langer’s lines. Neither type of incision affects the ease of the procedure, which can be considered as a normal median sternotomy. The incision is made into the subcutaneous tissue using an electric scalpel, and the rectus abdominis and linea alba are separated from the xiphoid process. A finger is inserted behind the sternum via the subxiphoid wound to blindly detach the caudal side of the thymus from the sternum. The linea alba, which has just been separated from the xiphoid process, can be felt by moving the finger caudally and is now separated approximately 1 cm caudally. The layer between the rear surface of the rectus abdominis and transversal fascia and peritoneum is blindly separated with the finger to create a space for port insertion. Caution should be exercised not to tear the peritoneum. If the peritoneum is torn, CO2 will enter the peritoneal cavity on insufflation and inflate the abdomen; however, this will have minimal impact on surgery. A GelPOINT Mini port (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA) for single-port surgery is inserted. This port enables insertion of three 10–12 mm child ports into the platform. The port base is gel, which helps prevent interference between instruments without over-fixation of the child ports.

A 5-mm rigid endoscope camera with a 30° perspective is used. CO2 insufflation is performed at 8 mmHg. The positive pressure of the insufflated CO2 displaces the lungs and pericardium dorsally, thereby expanding the space available for surgical manipulations. The surgeon holds a LigaSure Maryland type (Covidien, Mansfield, MA) vessel sealing device in the right hand and bent-tip grasping forceps designed for single-port usage (SILS Hand Instruments SILS clinch 36 cm; Covidien, Mansfield, MA) in the left hand. In single-port surgery, the use of bent-tip forceps is indispensable to avoid interference with the other forceps. The tip form of the LigaSure Maryland type is not only suitable for hemostasis and coagulotomy but also for separating tissue, which makes it suitable for this procedure. The trick to safe use of the LigaSure Maryland type device is to perform separation by opening and closing the jaw tips before dissection, passing one of the jaws through the separated area, and then dissecting. This manipulation is repeated during the procedure. Blind dissection without separation by opening and closing the jaws can result in accidental damage to crucial structures such as the brachiocephalic vein. The surgeon opens the bilateral mediastinal pleura to expose both sides of the thoracic cavity. In doing so, gravity causes the pericardium to shift dorsally, thereby further expanding the surgical space and making it easier to identify the bilateral phrenic nerves. The adipose tissue above the pericardium and thymus can then be separated from the pericardium anterior to the bilateral phrenic nerves. The left lobe of the thymus is pulled to the patient’s right with the forceps in the left hand and turned toward the right. The surgeon crosses over his hands to detach the left lobe using the LigaSure Maryland forceps in the right hand. To detach the right lobe of the thymus, the grasping forceps in the left hand are turned to the left, and the thymus is pulled to the patient’s left. At this point, the surgeon no longer needs to keep his hands crossed over (Figure 3). The thymus is detached from the pericardium in a caudal to cranial direction, which exposes the cranial side of the peripheral left brachiocephalic vein and the confluence of the medial left and right brachiocephalic veins. The superior poles of the thymus can then be dissected. The trick to manipulations of the neck area is to hold the superior poles of the thymus with clinch forceps in the left hand. Holding the superior poles of the thymus and pulling caudally pushes on the left brachiocephalic vein to improve the visual field of the neck. The superior poles of the thymus and adipose tissue of the neck are dissected at the right brachiocephalic vein on the right side, the thyroid gland on the cranial side, the brachiocephalic artery and trachea on the dorsal side, and the medial portion of the left brachiocephalic vein on the left side. Caution should be exercised so as not to injure the inferior thyroid vein. After detaching the adipose tissue of the neck on the cranial side from the left brachiocephalic vein, the thymus is pulled in either direction, thereby exposing the left brachiocephalic vein. The thymic vein is then sectioned with the vessel sealing device to complete the thymectomy.

In a subxiphoid single-port thymectomy, the thymic vein is sectioned last because it runs tangential to the subxiphoid wound and shifts laterally on the traction of the thymus. It is difficult to place the resected thymus into a bag with a shaft because the bag opening is tangential to the direction of forceps insertion. Instead, a bag without a shaft is inserted into the mediastinum, which the surgeon opens using forceps and then places the resected thymus into the bag. The thymus is removed from the body through the subxiphoid incision. A 20-Fr drain is inserted through the subxiphoid incision, and the wound is closed (Figure 4).

Bleeding management

During thymectomy, intraoperative bleeding is most likely to occur from the left brachiocephalic vein. In single-port surgery, pressure is applied to the point of bleeding using a cotton swab for thoracoscopy via the GelPOINT mini child port. If pressure does not stop the bleeding, the surgeon should promptly switch to median sternotomy. If pressure stops the bleeding, an additional 12-mm port with a valve should be placed in an intercostal space to ensure CO2 insufflation pressure on the left precordium for facilitating the left brachiocephalic approach. Port insertion must be performed while viewing the thoracic cavity to avoid damage to the heart. A TachoSil (Takeda Austria GmbH, Linz, Austria) is inserted through the port in the left precordium, and hemostasis is achieved by applying pressure to the point of bleeding a second time using a cotton swab for thoracoscopy. Wrapping the TachoSil with a small gauze will enable insertion without breaking.

Adoption of the subxiphoid approach

It is difficult for a surgeon inexperienced in the subxiphoid approach and single-port endoscopic surgery to rapidly adopt single-port thymectomy. As a first step, it is recommended to begin by performing subxiphoid dual-port thymectomy with an additional port in the right fifth intercostal space (7). The additional port is inserted via the intercostal space, which causes nerve damage in one intercostal space, but the extent of damage is less than the damage to multiple intercostal spaces caused by the lateral chest intercostal approach. The additional intercostal port reduces interference between surgical instruments and improves surgical operability.

Comments

Majority of the institutions perform endoscopic thymectomy with the lateral intercostal approach. This is due to thoracic surgeons’ familiarity with the intercostal approach; however, it is difficult to ensure the visual field of the neck and identify the contralateral phrenic nerve, and all patients experience postoperative intercostal nerve damage. We previously reported the subxiphoid single-port thymectomy with CO2 insufflation in 2012 (4). The operative field of the subxiphoid approach is the same as that of median sternotomy, which makes it easy to identify the neck structures and the location of the bilateral phrenic nerves, and there is no intercostal nerve damage because the intercostal approach is not used. Alternatives to performing the procedure with one incision below the xiphoid process include a method with two incisions below the xiphoid process (8) and approaches via the left and right intercostal space or neck as well as the subxiphoid port (7,9,10). In all these methods, the good visual field provided by the subxiphoid approach is helpful to the surgeon.

Few articles have reported the outcomes of thymectomy by the subxiphoid approach. The time required to perform single-port thymectomy is reportedly shorter, with less blood loss, shorter duration of drain placement, shorter hospital stay, and smaller doses and shorter duration of analgesic usage compared with that required to perform the lateral intercostal approach (11). Previous reports indicate that the subxiphoid approach, even with more than one port, is less invasive than the lateral intercostal approach (9). However, previous reports describing the usefulness of the subxiphoid approach were retrospective studies with small subject samples. Additional evidence based on larger case series with long-term outcomes is needed.

The subxiphoid approach affords a cervical field of view that is superior to other approaches and makes it easy to identify the bilateral phrenic nerves. Furthermore, it is a minimally invasive approach that reduces the extent of intercostal nerve damage compared with the lateral intercostal approach. Thymectomy using the subxiphoid approach is a surgical technique that should be learned by respiratory surgeons.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors Nuria Novoa and Wentao Fang for the series “Minimally Invasive Thymectomy” published in Mediastinum. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/med.2018.02.01). The series “Minimally Invasive Thymectomy” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Cooper JD, Al-Jilaihawa AN, Pearson FG, et al. An improved technique to facilitate transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 1988;45:242-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Landreneau RJ, Dowling RD, Castillo WM, et al. Thoracoscopic resection of an anterior mediastinal tumor. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;54:142-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugarbaker DJ. Thoracoscopy in the management of anterior mediastinal masses. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:653-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suda T, Sugimura H, Tochii D, et al. Single-port thymectomy through an infrasternal approach. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:334-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006;367:1618-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suda T. Subxiphoid single-port thymectomy procedure. Asvide 2018;5:126. Available online: http://www.asvide.com/article/view/23400

- Suda T, Ashikari S, Tochii D, et al. Dual-port thymectomy using subxiphoid approach. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;62:570-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kido T, Hazama K, Inoue Y, et al. Resection of anterior mediastinal masses through an infrasternal approach. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:263-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yano M, Moriyama S, Haneda H, et al. The Subxiphoid Approach Leads to Less Invasive Thoracoscopic Thymectomy Than the Lateral Approach. World J Surg 2017;41:763-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zieliński M, Kuzdzał J, Szlubowski A, et al. Transcervical-subxiphoid-videothoracoscopic "maximal" thymectomy--operative technique and early results. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:404-9; discussion 409-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suda T, Hachimaru A, Tochii D, et al. Video assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy versus subxiphoid single-port thymectomy: initial results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:i54-8. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Suda T. Subxiphoid single-port thymectomy procedure: tips and pitfalls. Mediastinum 2018;2:15.