具有重症肌无力的胸腺病理学

简介

MG是一种自身免疫性疾病,通过对各种蛋白质的自身抗体攻击,引起肌肉疲劳和虚弱,这些蛋白质在生理和功能上相互协作,稳定了位于神经肌肉连接处突触后褶皱尖端的高度有序和密集排列的AChRs,作为维持高效神经肌肉信号转导的先决条件[1,2]。各种自身抗体的“靶点异质性”伴随着不同的临床表现、不同的发病机制、不同的遗传危险因素以及不同的病变[3]。目前MG被分为:

- 具有抗AChR自身抗体的MG(即AChR-MG),即最普遍的MG类型,发生在70%~80% 的MG患者中,主要是由于补体激活抗肌肉型AChR的IgG1自身抗体[1,4]。这个类型包括最近被认为是“血清反应阴性”的患者,因为他们的自身抗体不结合可溶性AChRs(用于常规放射免疫分析的靶点),而仅识别AChRs的簇状结构,需要细胞学实验来识别[5];

- 具有针对MuSK抗体的MG(即MuSK-MG)[6],这主要是由于IgG4抗体的补体独立干扰MuSK/低密度脂蛋白受体相关蛋白4(low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4,LRP4)交互作用[7];

- 基于主要是补体激活针对LRP4的IgG1和IgG2抗体的MG(即LRP4-MG),LRP4是与MuSK交互作用的伙伴[8-10];

- 具有针对运动神经元源性LRP4配体和agrin 的自身抗体的MG(即Agrin -MG)[11,12];

- 未知靶向自身抗原的MG,暂且称作“四重血清反应阴性(quadruple sero-negative,qSN)的MG”(即qSN -MG)[13,14]。

此外,有一小部分“双重血清阳性”的MG患者具有不只一种上述提到的肌无力相关的自身抗体,如 AChR/LRP4-MG[13,15]、AChR/agrin-MG [12,13]、MuSK/LRP4-MG[8,16]和很少的AChR/MuSK MG[17,18]。当胸腺瘤切除后,AChR-MG可转换为AChR/LRP4-MG[19],并且在对具有早发性重症肌无力(early onset myasthenia gravis,EOMG)[20]的胸腺切除多年后也能观察到该变化。

MG复杂性的另一个维度来自于AChR-MG的异质性,根据流行病学、遗传学、临床和胸腺病理基础,可细分为胸腺瘤相关性MG(thymoma-associated MG,TAMG)、非胸腺瘤性MG、EOMG和迟发性MG(late onset MG,LOMG)。此外,在许多AChR-MG患者中,除AChR外的各种自身免疫靶点也会受到自身抗体的攻击,从而导致伴有临床高度相关和潜在生命威胁的疾病,如EOMG患者所发生的自身免疫性甲状腺疾病、系统性红斑狼疮或I型糖尿病;自身免疫性纯红细胞发育不全、血细胞减少、低丙种球蛋白血症(Good综合征)、脑炎和TAMG伴发的许多其他疾病[21,22]。尽管TAMG(胸腺肿瘤)和EOMG(胸腺“萎缩”)时的胸腺病理完全不同,但在TAMG和LOMG中具有诊断意义的抗肌联蛋白自身抗体和抗各种细胞因子的自身抗体方面却有着惊人的免疫学重叠[23,24]。

在罕见的胸腺脂肪瘤患者中,MG的患病率似乎要高于健康人群,在最近的一项研究中,267例MG相关的胸腺切除术中有4.4%发现了胸腺脂肪瘤,并且在胸腺切除术后MG达到稳定缓解的患者比例与在EOMG患者中观察到的该术后比例相似(约42%)[25]。迄今为止,所描述的全部胸腺脂肪瘤相关性MG(thymolipoma-associated MG,TLAMG)患者似乎都患有AChR-MG。对这一小群MG患者的研究还不够充分,从而无法对疾病机制进行有意义的推测。

在最近的文献中给出了关于AChR-MG的流行病学、免疫学和临床异质性的详细描述[1,2]。有趣的是,几项流行病学研究显示,由于不明原因,老年人的LOMG(即AChR-MG)确实增加了[26,27]。报道的AChR-MG发病率在每百万人中为1-14(平均为7),差别还是很大的[27]。

关于导致不同MG类型的主要病因和致病途径的描述超出了本文的范畴,可以在最近的文献中获得[1,7,28]。我们在本文重点叙述的是MG患者中反复遇到的各种胸腺病变病理相关性内容(表1),也简短地讨论与非胸腺肿瘤相关的MG,但不涉及胸腺癌(thymic carcinomas,TCs)。TCs也是起源于胸腺上皮细胞,因类似其他部位的癌而被标记为鳞状细胞癌。由于TCs通常缺乏胸腺功能(如肿瘤内胸腺发育),相关的自身免疫疾病很少见(如多发性肌炎)或几乎不存在(如MG)。关于MG相关的TCs报道可能源于以下事实(Ⅰ)B3型胸腺瘤曾经被称为“分化良好的胸腺癌”[36]而难以与TCs区分;(Ⅱ)混合性癌肿中伴有TCs的肌无力性胸腺瘤成分未被识别出来。

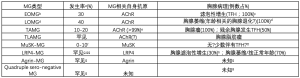

Full table

胸腺滤泡性增生(TFH)

具有TFH的胸腺显示髓质和血管周围可见淋巴滤泡增多。皮质类固醇激素缺乏症患者的胸腺皮质和髓质结构是符合年龄段特征的。虽然单个淋巴滤泡可能发生在健康人中[38-40],但超过三分之一的胸腺小叶中出现的滤泡则可能是病理性的[41]。

很多自身免疫性疾病可与TFH相关[3],但TFH在EOMG中最常见,即非胸腺瘤性AChR-MG患者大多小于50岁,可能很少超过55岁(在男性)和65岁(在女性)[29]。由EOMG引起的TFH发病率为1-10/100万/年[42]。TFH在TAMG时的胸腺瘤邻近残余胸腺中也很常见(30%~50%),并被认为是自身抗体的来源[43]。相比之下,报道的THF在MuSK-MG(21%)、LRP4-MG(0%~31%)和AChR(-)/MuSK(-)/ LRP4(-)三阴性MG(22%)中的发生率[16]需要确认。TFH的始发机制尚不清楚,但EOMG的胸腺内发病机理的很多后续步骤已被解决,从而导致胸腺内部自身抗体的产生[1,43]。由于EOMG时在胸腺内部产生的自身抗体高于其外部,所以胸腺被认为是EOMG中自身免疫的主要位点[44],这也为早期胸腺切除术提供了依据[35]。

临床上认为:与胸腺瘤和“真性胸腺增生”相比[45],TFH不会引起局部症状。TFH时的全身症状是由潜在的自身免疫性疾病引起的。

肉眼观察:TFH时胸腺的重量和大小,按对应的年龄而言是正常或略有增加的[38]。当经皮质类固醇治疗后,常见明显的胸腺收缩。

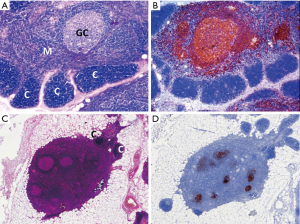

组织学和免疫组织化学:皮质类固醇激素缺乏症患者的胸腺呈现正常年龄皮质,皮质区具有末端脱氧核苷酸转移酶(terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase,TdT)+的未成熟T细胞,而淋巴滤泡发生处的髓质区扩大(图1)。滤泡显示CD21+/ CD23+/CD35+的FDC网,可能显示也可能不显示反应性的生发中心。Hassall小体数目正常。正常情况下连续的上皮网将髓质与无上皮的血管周间隙分隔开,TFH时淋巴滤泡破坏了上述结构,从而导致含有B细胞和T细胞数量增加的两种区域的融合和扩大[46]。持续的TFH可诱导胸腺上皮增生。皮质类固醇治疗可导致胸腺皮质出现星空图案和收缩,以及生发中心和FDC网的塌陷。长时间、高剂量的皮质类固醇和硫唑嘌呤治疗可完全破坏皮质结构和TFH[47],诱导髓质收缩,并可消除Hassall小体。并有一种TFH分级系统被提出[41]。CD21、CD23或CD35的FDC网着色有助于识别早期的TFH和皮质类固醇治疗后的残留滤泡[41]。

鉴别诊断:在MG相关的B1型和B2型胸腺瘤中,可出现邻近TdT+淋巴细胞丰富的皮质结构的淋巴滤泡。在小活检中,厚的纤维囊结构或者邻近纤维间隔的髓质岛(medullary islands,MIs)提示B1型胸腺瘤,而上皮细胞数量的增加和簇集则提示B2型胸腺瘤[48]。虽然“单纯的”伴淋巴样间质的微结节型胸腺瘤(micronodular thymoma,MNT)通常与MG无关,但伴微结节成分的A型或AB型胸腺瘤可伴有MG。在小活检中,梭形上皮细胞结节可提示准确诊断。对MG相关胸腺瘤旁的TFH残留胸腺取样是小活检时的一个陷阱,这强调了将组织学与影像学所见相结合的必要性。在许多其他与淋巴滤泡相关的纵隔疾病中,MG通常不存在,包括纵隔囊肿(若没有与EOMG或TAMG)相关[49]、“单纯的”TCs (如前所述)、生殖细胞肿瘤、淋巴瘤和“LESA样”胸腺增生[50],而显示MG状态的信息也有助于解读小胸腺活检。

胸腺瘤

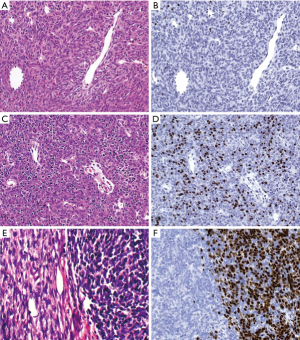

10%~20%的MG患者存在胸腺瘤,30%的胸腺瘤患者患有TAMG。TAMG通常发生于40岁以后,但也可能影响儿童。胸腺瘤是上皮性肿瘤,根据WHO分类将其分为A型、AB型、B1型、B2型、B3型和其他类型。它们通常保持胸腺功能(如瘤内胸腺发育)。由于这种胸腺发育不能诱导免疫耐受,胸腺瘤通常与自身免疫性疾病有关,最常见的是MG[3]。在这里,我们将讨论可能会与MG相关的A型、AB型、B1型、B2型和B3型胸腺瘤(表2)。

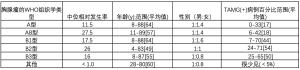

Full table

A型胸腺瘤,包括‘非典型A型胸腺瘤’变异型

A型胸腺瘤是一种临床上惰性的肿瘤,由温和的梭形/卵圆形上皮细胞组成,混杂很少或没有混合的未成熟T细胞。更具侵袭性的非典型变异型可表现为细胞增多、有丝分裂活性高和局灶性坏死,而后者与侵袭性增加有关。分期分布见参考文献[51]。由于A型胸腺瘤是一种淋巴细胞贫乏或无淋巴细胞的肿瘤,因此很少与MG相关。

肉眼观察,A型胸腺瘤通常被包膜或边界清楚(I期或II期)。非典型变异型胸腺瘤可能边界不清,可侵犯邻近器官并出现转移[52-54]。

组织学上(图2A,图2B,图2C,图2D),A型胸腺瘤呈现束状、席纹状、腺腔/腺样、实性、菊形团样、血管外皮瘤样和副神经节瘤样的形态。瘤细胞为温和的梭形或卵圆形,胞核小而呈纺锤形或卵圆形,核染色质细,核仁不明显,几乎在所有病例中均可见薄壁的血管外皮瘤样血管。瘤细胞也可呈多角形。淋巴细胞稀少。有丝分裂、凋亡细胞和血管周围间隙少见。出现凝固性坏死是非典型变异型的特征。Hassall小体缺失。

免疫组化方面,A型胸腺瘤没有或罕见有TdT(+)/CD99(+)/CD1a(+)的未成熟T细胞,后者首选TdT标记。在>10%的可评估肿瘤区域中,若有任何“拥挤的”的或数量适中的未成熟T细胞,则提示诊断为AB型胸腺瘤。上皮细胞一致性表达CK19和p63/p40,通常CD20(+)(局灶性的),而CK20、CD5和CD117均为阴性。在通常的A型胸腺瘤中,Ki-67增殖指数<2%[55],而在非典型变异型中可能更高(据作者观察)。

从遗传学角度来看,反复的结构遗传改变是罕见的[56],而GTF2I基因独特的点突变(L404H)在所有胸腺瘤中发生率是最高的(80%)。

鉴别诊断包括其他梭形细胞“病变”:AB型胸腺瘤、伴局灶梭形细胞的B3型胸腺瘤、肉瘤样癌、梭形细胞类癌;黑色素瘤、滑膜肉瘤、孤立性纤维性肿瘤、炎性肌纤维母细胞肿瘤、神经鞘瘤、间皮瘤和树突状细胞肿瘤。

对于“非典型的”病例,完全的手术切除是唯一确切却可能比较困难的治疗方法[54]。10年生存率可达80%~100%[58,59],但非典型变异型的生存率尚不清楚。

AB型胸腺瘤

AB型胸腺瘤是一种惰性的上皮性肿瘤,具有不同比例的淋巴细胞贫乏(A型)成分和淋巴细胞丰富(B样)成分。B样成分不能是B型胸腺瘤类型的形态(比如像B1型或B2型那样的)。分期分布见参考文献[51]。MG可发生在20%~40%的病例,且其他自身免疫性疾病也很常见[22]。

大体观察,大多数病例境界清楚。类似于非典型A型胸腺瘤的不典型病例(如伴有坏死、广泛侵袭、转移)是罕见的(<5%)[52]。

组织学和免疫组化方面(图2C,图2D,图2E,图2F),A型区域类型与A型胸腺瘤相似。B样区显示梭形、椭圆形或罕见的多角形肿瘤细胞,瘤细胞核小,核仁不明显,也就是说不像B型胸腺瘤的肿瘤细胞。可出现淡染的MIs。很少情况下,AB型胸腺瘤是不成熟的富含T细胞的,即A型区域和双相模式不是诊断的必要条件。梭形的和CD20(+)的肿瘤细胞有助于识别此类病例。与B1型胸腺瘤不同,AB型胸腺瘤的上皮细胞具有丰富的角蛋白及p63/p40染色。50%的病例出现局灶性的上皮细胞CD20阳性。上皮细胞膜抗原(epithelial membrane antigen,EMA)在间隔结构中的阳性表达是另一个有用的特征[60]。髓质岛外淋巴细胞主要是CD3(+) TdT(+)、Ki-67增殖指数>90%的未成熟T细胞。

遗传学方面,其结构改变比A型胸腺瘤更常见[56],而热点GTF2I突变也同样普遍(见于74%~80%的病例)。

鉴别诊断包括A型、B1型、B2型胸腺瘤和伴淋巴样间质的MNT。在MNTs中,淋巴样成分在上皮成分外部。以A型或AB型胸腺瘤和MNT成分为特征的肿瘤是常见的,可能与MG有关。

由于肿瘤分期通常较低,完全切除是唯一可行的治疗方法。10年总生存率超过80%[58,59]。

B1型胸腺瘤

B1型胸腺瘤与正常儿童胸腺相似,有大量的未成熟T细胞,缺乏上皮细胞且没有上皮细胞聚集,占优势的皮质区域与较小的‘MIs’呈现“器官样”的共同排列。Hassall小体不是必须存在的。至于分期分布见参考文献[51]。MG常见(45%),其他自身免疫性疾病少见(5%)。单纯的B1型胸腺瘤通常是惰性肿瘤(I期和II期占比>80%)[58,59]。

大体观察,大多数B1型胸腺瘤境界清楚。大部分包膜坚实而内部柔软。肿瘤结节通常较大,被纤细或粗糙的纤维间隔分隔。

组织学和免疫组化方面(图3A,图3B),B1型胸腺瘤很少或没有分叶。深色的皮质区域要比浅色的MIs占优势。然而,MIs并不像儿童胸腺那样始终埋藏在皮质区,而是经常错位到肿瘤小叶或纤维间隔的周围。Hassall小体出现在50%的病例中,但通常不是在所有的MIs中。丰富的上皮细胞应当与正常的儿童胸腺相似,且缺乏簇集(即3个或更多相邻的肿瘤细胞)(最好在p40/p63染色中观察)。肿瘤细胞具有泡状染色质和突出程度不等的核仁。免疫组化染色显示纤细的细胞角蛋白阳性的上皮细胞网,并在MIs中减弱。在皮质区CD3(+)TdT(+)T细胞在占优势,在MIs中,CD3(+)/TdT(-)T细胞则要超过CD20(+)B细胞从而占优。在50%的病例中,(某些)MIs中出现Desmin(+)肌样细胞和自身免疫调节因子(autoimmune regulator,AIRE)(+)的上皮细胞。

从遗传学上讲,染色体的获得和丢失不像更具侵袭性的B2型和B3型胸腺瘤那样频繁[56]。32%的病例出现GTF2I突变[57]。

鉴别诊断包括正常胸腺、反弹性增生、真性胸腺增生和T淋巴母细胞淋巴瘤(T-lymphoblastic lymphoma,T-LBL),所有这些都与MG无关。在小活检中,可能无法区分正常胸腺、TFH和B1型胸腺瘤(伴淋巴滤泡)。皮质大于髓质,错位的MIs和缺乏Hassall小体有助于B1型胸腺瘤的诊断。AB型胸腺瘤的B样区域可通过梭形细胞和大量角蛋白(+)的上皮细胞而识别出来,它们在50%的病例中呈CD20(+)。而B2型胸腺瘤显示肿瘤细胞数量增多或呈簇状。

超过90%的B1型胸腺瘤通过切除可治愈;10年和20年的生存率为85%~100%[58,59]。

B2型胸腺瘤

B2型胸腺瘤是富含TdT(+)T细胞的侵袭性肿瘤,与B1型胸腺瘤相比,其多角形和树突状肿瘤细胞数量增加。而梭形肿瘤细胞缺乏。

至于分期分布见参考文献[51]。在儿童中发病是罕见的[61]。MG在高达50%的病例中发生[59],单纯的红细胞发育不全和低丙种球蛋白血症少见(5%)。胸腔积液和腔静脉综合征比A型、AB型和B1型胸腺瘤更常见。大体观察B2型胸腺瘤常浸润纵隔脂肪、胸膜、肺、心脏或大血管。切面呈灰白色,质硬,并且可能出现分隔不良、坏死、出血和囊肿。

组织学和免疫组化方面(图3C, 图3D),肿瘤常被纤维间隔分隔成小叶结构。众多TdT(+)的T细胞赋予肿瘤蓝色的感觉。肿瘤细胞核内染色质呈泡状,核仁明显。血管周围间隙和MIs可出现或缺乏Hassall小体。在MG(+)病例中常见瘤内淋巴滤泡。角蛋白/p40(+)的肿瘤细胞数量比B1型胸腺瘤更多,可成簇出现(3个或更多相邻的上皮细胞)。在40%的B2型胸腺瘤中可出现少量B3型或B1型胸腺瘤成分。

在遗传学上,B2型胸腺瘤结构改变的数量介于AB型和B3型胸腺瘤之间[56]。22%的B2型胸腺瘤具有热点GTF2I突变[57]。

鉴别诊断包括B1型胸腺瘤和T-LBL(如前所述)。B2型胸腺瘤很少出现角蛋白表达缺失[62]。由于在这些病例中,p40的表达通常保持稳定,如果B2型胸腺瘤和T-LBL的鉴别诊断出现困难,则推荐使用p40染色。

70%~90%的病例能完全切除,且R0切除的II期和III期的B2型胸腺瘤10年复发率分别达到32%和41%。总的来说,10年生存率为70%~90%[58,59,63]。

B3型胸腺瘤

B3型胸腺瘤是上皮细胞为主性的肿瘤,有少量或没有不成熟的TdT(+)T细胞。大部分瘤细胞丧失了皮质和髓质特征[64]。分期分布见参考文献[51]。儿童罕见发生[61]。MG在40%~50%的病例中发生,其他自身免疫性疾病很少见。局部症状比其他胸腺瘤更常见。

大体观察,B3型胸腺瘤常浸润纵隔脂肪及邻近器官。切面实性或质硬,呈灰色/白色,常见出血、坏死和囊肿。

组织学和免疫组化方面(图3E, 图3F),肿瘤小叶由多角形肿瘤细胞构成,给人粉红色印象。在侵袭前沿,小叶轮廓大多清晰且无单个细胞浸润,而单个细胞浸润在TC中更常见。肿瘤细胞胞核要么温和(无明显核仁),要么呈中度不典型,核仁突出。在肿瘤细胞间通常有少数或几乎没有淋巴细胞,后者可能表达TdT(+)或不表达。血管周围间隙通常很明显。可出现Hassall小体、局灶梭形细胞和透明细胞。角蛋白及p40/p63呈弥漫性致密表达;仅局灶表达GLUT1[65]和EMA,CD20无表达。CD5和CD117的局灶表达很少见。

从遗传学角度看,B3型胸腺瘤在所有胸腺瘤中的基因改变发生率最高[56],而GTF2I热点突变(21%)与B2型胸腺瘤一样常见[57]。

鉴别诊断:与B2型胸腺瘤的鉴别点在于HE切片中B3型胸腺瘤呈粉红色表现(图3E),而B2型呈蓝色表现(图3C)。若未取材到具有典型特征的区域(如CD20表达、腺样结构、突出的血管周围间隙),伴局灶梭形细胞的B3型胸腺瘤与A型胸腺瘤在小活检中可能无法区分。有时胸腺鳞状细胞癌(thymic squamous cell carcinomas,TSQCC)可能也难以鉴别,因为罕见情况下它们可以在侵袭前沿显示血管周围间隙和清晰的轮廓。在MG存在的情况下,TSQCC的诊断应谨慎,并辅以寻找胸腺瘤成分。突出的细胞间桥,CD5和CD117的表达(见于80%的TSQCC),GLUT1弥漫性阳性,以及缺乏TdT+的T细胞,则提示TSQCC的诊断[51]。神经内分泌肿瘤、生殖细胞肿瘤、肉瘤、间皮瘤和甲状旁腺腺瘤可能被误诊为B3型胸腺瘤或TC。

治疗方面与B2型胸腺瘤相似。30%的B3型胸腺瘤在10年内复发[58]。10年总生存率为50%~70% [59,63]。早期发现的MG(+)病例预后较好。

胸腺萎缩

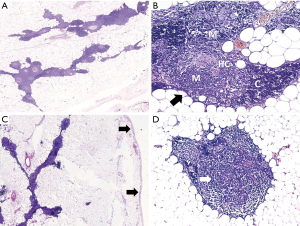

长期以来,胸腺萎缩一直被认为是与LOMG相关的典型“病理表现”,即老年人的非胸腺瘤性AChR-MG[见参考文献[3]]。随着年龄的增长,胸腺的淋巴上皮组织逐渐被脂肪取代,皮质-髓质结构变得扭曲(髓质结构与脂肪组织相邻)(图4A,图4B),但至少到中年,残瘤的实质仍继续输出一些T细胞[29,67]。在LOMG中,这些残留组织的形态学分析没有显示LOMG与正常胸腺之间的显著差异[38]。LOMG中胸腺肌样细胞稀少[68],随着年龄增长而下降,到60岁和70岁时几乎不能查见,且患者之间差异很大[69]。AIRE阳性细胞的数量也在下降(据作者观察),然而,LOMG和以年龄匹配作对照的胸腺之间也没有明显差异,这表明LOMG状态下的“萎缩”可能被当作(生理性的)“退化”。然而,目前LOMG患者的非组织学特征强烈提示胸腺参与了LOMG的发病机制。这些特征包括(Ⅰ) TAMG(其中肯定涉及肿瘤性的胸腺组织)和LOMG之间在抗横纹肌(主要是抗肌联蛋白)和抗细胞因子自身抗体方面的独特免疫性重叠[23,24];(Ⅱ)LOMG患者胸腺输出的naïve T细胞似乎明显少于与年龄匹配的对照组[29]。

了解LOMG胸腺的这些功能特性可能会揭示组织标志物,从而用于未来在免疫组化水平上识别胸腺异常。

最近,在MuSK-MG[34,46]或LRP4-MG[13,16]患者的一些个体中,胸腺萎缩也被认为是一种“病理表现”。与LOMG的情况一样,对于MuSK-MG [70] 和LRP4-MG [2]的胸腺切除通常并不获益,只有少数例外[71]。这些观察结果与MuSK-MG胸腺切除标本中的组织学发现基本一致[34,46],而在LRP4-MG胸腺中进行类似的标准化形态学研究尚待进行,对于MuSK-MG和LRP4-MG患者中进行功能性研究(例如胸腺T细胞输出)也是如此。

胸腺脂肪瘤

胸腺脂肪瘤在胸腺肿瘤中很少见,占所有病例的2%~9%,可发生在任何年龄,没有明显的性别倾向[25]。组织学上(图4C,图4D),该肿瘤由胸腺组织的一小部分组成,内嵌于成熟脂肪组织的主要成分中,整体被纤维性、无上皮的包膜所包裹。胸腺成分通常萎缩,很少表现出滤泡性增生和异常的肿瘤转化(胸腺瘤或类癌)[51,72]。胸腺脂肪瘤已多次被发现与MG相关,而在纵隔/胸腺内发生的脂肪瘤却并非如此,这表明胸腺成分和TLAMG之间可能存在一种致病(即非偶然的)联系[25,73-75]。另一方面,在罕见的报道[73,75,76]中,MG患者在胸腺脂肪瘤患者中的比例差异很大(2%~50%),这使风险预测成为一种投机性推断。TLAMG显然是与胸腺脂肪瘤相关的最常见的自身免疫性疾病,而低丙种球蛋白血症(Good综合征)[77]、红细胞发育不良[78]、再生障碍性贫血、多发性肌炎[79]和Graves病的报道较少[73]。上述后一种罕见的自身免疫性疾病在那些TLAMG患者表明TLAMG和TAMG之间存在相似性,但没有免疫学数据(例如抗肌联蛋白或抗细胞因子自身抗体)支持这一假设。最后,对于胸腺脂肪瘤伴TLAMG,尚无具有一致性组织学改变(如滤泡增生或萎缩)的报道[80]。

其他恶性肿瘤并发MG

胸腺外上皮性、间充质性和血液性的恶性肿瘤很少被报道与MG相关,这可能反映了偶然的巧合或非特异性免疫紊乱的结果[81,82]。然而,在罕见的MG相关横纹肌肉瘤(rhabdomyosarcoma,RMS)中,可能发生了针对 AChRs的自身免疫“意外”[83]。这种独特的RMS“意外”的起因仍是个谜,不能用AChR的表达来解释,因为几乎所有的RMS都表达功能性 AChRs[84]。MG相关的非胸腺恶性肿瘤可能需要更多的关注,例如发生在纵隔[85]和肠系膜[86]的罕见AChR-MG相关FDC肉瘤。上述两种病例都是首批被描述为胸腺瘤样瘤内胸腺发育的非胸腺上皮肿瘤,并提示这一特性与副肿瘤性MG有关。

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor Mirella Marino for the series “Diagnostic Problems in Anterior Mediastinum Lesions” published in Mediastinum. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/med.2018.12.04). The series “Diagnostic Problems in Anterior Mediastinum Lesions” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Romi F, Hong Y, Gilhus NE. Pathophysiology and immunological profile of myasthenia gravis and its subgroups. Curr Opin Immunol 2017;49:9-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classification and therapeutic strategies. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:1023-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marx A, Pfister F, Schalke B, et al. The different roles of the thymus in the pathogenesis of the various myasthenia gravis subtypes. Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:875-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patrick J, Lindstrom J. Autoimmune response to acetylcholine receptor. Science 1973;180:871-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leite MI, Jacob S, Viegas S, et al. IgG1 antibodies to acetylcholine receptors in 'seronegative' myasthenia gravis. Brain 2008;131:1940-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoch W, McConville J, Helms S, et al. Auto-antibodies to the receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK in patients with myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. Nat Med 2001;7:365-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huijbers MG, Zhang W, Klooster R, et al. MuSK IgG4 autoantibodies cause myasthenia gravis by inhibiting binding between MuSK and Lrp4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:20783-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang B, Tzartos JS, Belimezi M, et al. Autoantibodies to lipoprotein-related protein 4 in patients with double-seronegative myasthenia gravis. Arch Neurol 2012;69:445-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pevzner A, Schoser B, Peters K, et al. Anti-LRP4 autoantibodies in AChR- and MuSK-antibody-negative myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 2012;259:427-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higuchi O, Hamuro J, Motomura M, et al. Autoantibodies to low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 in myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol 2011;69:418-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gasperi C, Melms A, Schoser B, et al. Anti-agrin autoantibodies in myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2014;82:1976-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang B, Shen C, Bealmear B, et al. Autoantibodies to agrin in myasthenia gravis patients. PLoS One 2014;9:e91816 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cordts I, Bodart N, Hartmann K, et al. Screening for lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4-, agrin-, and titin-antibodies and exploring the autoimmune spectrum in myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 2017;264:1193-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zisimopoulou P, Brenner T, Trakas N, et al. Serological diagnostics in myasthenia gravis based on novel assays and recently identified antigens. Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:924-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa H, Taniguchi A, Ii Y, et al. Double-seropositive myasthenia gravis with acetylcholine receptor and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 antibodies associated with invasive thymoma. Neuromuscul Disord 2017;27:914-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zisimopoulou P, Evangelakou P, Tzartos J, et al. A comprehensive analysis of the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of anti-LRP4 in myasthenia gravis. J Autoimmun 2014;52:139-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong Y, Zisimopoulou P, Trakas N, et al. Multiple antibody detection in 'seronegative' myasthenia gravis patients. Eur J Neurol 2017;24:844-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zouvelou V, Kyriazi S, Rentzos M, et al. Double-seropositive myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2013;47:465-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jordan B, Schilling S, Zierz S. Switch to double positive late onset MuSK myasthenia gravis following thymomectomy in paraneoplastic AChR antibody positive myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 2016;263:174-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zouvelou V, Zisimopoulou P, Psimenou E, et al. AChR-myasthenia gravis switching to double-seropositive several years after the onset. J Neuroimmunol 2014;267:111-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marx A, Porubsky S, Belharazem D, et al. Thymoma related myasthenia gravis in humans and potential animal models. Exp Neurol 2015;270:55-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marx A, Willcox N, Leite MI, et al. Thymoma and paraneoplastic myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity 2010;43:413-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kisand K, Lilic D, Casanova JL, et al. Mucocutaneous candidiasis and autoimmunity against cytokines in APECED and thymoma patients: clinical and pathogenetic implications. Eur J Immunol 2011;41:1517-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meager A, Wadhwa M, Dilger P, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies in autoimmunity: preponderance of neutralizing autoantibodies against interferon-alpha, interferon-omega and interleukin-12 in patients with thymoma and/or myasthenia gravis. Clin Exp Immunol 2003;132:128-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang CS, Li WY, Lee PC, et al. Analysis of outcomes following surgical treatment of thymolipomatous myasthenia gravis: comparison with thymomatous and non-thymomatous myasthenia gravis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;18:475-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carr AS, Cardwell CR, McCarron PO, et al. A systematic review of population based epidemiological studies in Myasthenia Gravis. BMC Neurol 2010;10:46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heldal AT, Eide GE, Gilhus NE, et al. Geographical distribution of a seropositive myasthenia gravis population. Muscle Nerve 2012;45:815-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilhus NE, Verschuuren JJ. Myasthenia gravis: subgroup classifications - Authors' reply. Lancet Neurol 2016;15:357-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chuang WY, Strobel P, Bohlender-Willke AL, et al. Late-onset myasthenia gravis - CTLA4(low) genotype association and low-for-age thymic output of naive T cells. J Autoimmun 2014;52:122-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saka E, Topcuoglu MA, Akkaya B, et al. Thymus changes in anti-MuSK-positive and -negative myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2005;65:782-3; author reply -3.

- Rigamonti A, Lauria G, Piamarta F, et al. Thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis without acetylcholine receptor antibodies. J Neurol Sci 2011;302:112-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maggi L, Andreetta F, Antozzi C, et al. Two cases of thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis without antibodies to the acetylcholine receptor. Neuromuscul Disord 2008;18:678-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leite MI, Strobel P, Jones M, et al. Fewer thymic changes in MuSK antibody-positive than in MuSK antibody-negative MG. Ann Neurol 2005;57:444-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lauriola L, Ranelletti F, Maggiano N, et al. Thymus changes in anti-MuSK-positive and -negative myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2005;64:536-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolfe GI, Kaminski HJ, Aban IB, et al. Randomized Trial of Thymectomy in Myasthenia Gravis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:511-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kirchner T, Schalke B, Buchwald J, et al. Well-differentiated thymic carcinoma. An organotypical low-grade carcinoma with relationship to cortical thymoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:1153-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim SH, Koh IS, Minn YK. Pathologic Finding of Thymic Carcinoma Accompanied by Myasthenia Gravis. J Clin Neurol 2015;11:372-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strobel P, Moritz R, Leite MI, et al. The ageing and myasthenic thymus: a morphometric study validating a standard procedure in the histological workup of thymic specimens. J Neuroimmunol 2008;201-202:64-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Middleton G, Schoch EM. The prevalence of human thymic lymphoid follicles is lower in suicides. Virchows Arch 2000;436:127-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okabe H. Thymic lymph follicles; a histopathological study of 1,356 autopsy cases. Acta Pathol Jpn 1966;16:109-30. [PubMed]

- Marx A, Pfister F, Schalke B, et al. Thymus pathology observed in the MGTX trial. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012;1275:92-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyer A, Levy Y. Geoepidemiology of myasthenia gravis Autoimmun Rev 2010;9:A383-6. [corrected]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vincent A, Scadding GK, Thomas HC, et al. In-vitro synthesis of anti-acetylcholine-receptor antibody by thymic lymphocytes in myasthenia gravis. Lancet 1978;1:305-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hohlfeld R, Wekerle H. Reflections on the “intrathymic pathogenesis” of myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol 2008;201-202:21-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weis CA, Markl B, Schuster T, et al. True thymic hyperplasia: Differential diagnosis of thymic mass lesions in neonates and children. Pathologe 2017;38:286-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leite MI, Jones M, Strobel P, et al. Myasthenia gravis thymus: complement vulnerability of epithelial and myoid cells, complement attack on them, and correlations with autoantibody status. Am J Pathol 2007;171:893-905. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schalke BC, Mertens HG, Kirchner T, et al. Long-term treatment with azathioprine abolishes thymic lymphoid follicular hyperplasia in myasthenia gravis. Lancet 1987;2:682. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marx A, Chan JK, Coindre JM, et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Thymus: Continuity and Changes. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:1383-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suster S, Rosai J. Multilocular thymic cyst: an acquired reactive process. Study of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1991;15:388-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weissferdt A, Moran CA. Thymic hyperplasia with lymphoepithelial sialadenitis (LESA)-like features: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 4 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 2012;138:816-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC; 2015.

- Green AC, Marx A, Strobel P, et al. Type A and AB thymomas: histological features associated with increased stage. Histopathology 2015;66:884-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nonaka D, Rosai J. Is there a spectrum of cytologic atypia in type a thymomas analogous to that seen in type B thymomas? A pilot study of 13 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:889-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jain RK, Mehta RJ, Henley JD, et al. WHO types A and AB thymomas: not always benign. Mod Pathol 2010;23:1641-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roden AC, Yi ES, Jenkins SM, et al. Diagnostic significance of cell kinetic parameters in World Health Organization type A and B3 thymomas and thymic carcinomas. Hum Pathol 2015;46:17-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajan A, Girard N, Marx A. State of the art of genetic alterations in thymic epithelial tumors. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:S131-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Petrini I, Meltzer PS, Kim IK, et al. A specific missense mutation in GTF2I occurs at high frequency in thymic epithelial tumors. Nat Genet 2014;46:844-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weis CA, Yao X, Deng Y, et al. The impact of thymoma histotype on prognosis in a worldwide database. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:367-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strobel P, Bauer A, Puppe B, et al. Tumor recurrence and survival in patients treated for thymomas and thymic squamous cell carcinomas: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:1501-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weissferdt A, Hernandez JC, Kalhor N, et al. Spindle cell thymomas: an immunohistochemical study of 30 cases. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2011;19:329-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stachowicz-Stencel T, Orbach D, Brecht I, et al. Thymoma and thymic carcinoma in children and adolescents: a report from the European Cooperative Study Group for Pediatric Rare Tumors (EXPeRT). Eur J Cancer 2015;51:2444-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adam P, Hakroush S, Hofmann I, et al. Thymoma with loss of keratin expression (and giant cells): a potential diagnostic pitfall. Virchows Arch 2014;465:313-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okumura M, Ohta M, Tateyama H, et al. The World Health Organization histologic classification system reflects the oncologic behavior of thymoma: a clinical study of 273 patients. Cancer 2002;94:624-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strobel P, Hartmann E, Rosenwald A, et al. Corticomedullary differentiation and maturational arrest in thymomas. Histopathology 2014;64:557-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas de Montpreville V, Quilhot P, Chalabreysse L, et al. Glut-1 intensity and pattern of expression in thymic epithelial tumors are predictive of WHO subtypes. Pathol Res Pract 2015;211:996-1002. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Jong WK, Blaauwgeers JL, Schaapveld M, et al. Thymic epithelial tumours: a population-based study of the incidence, diagnostic procedures and therapy. Eur J Cancer 2008;44:123-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Douek DC, McFarland RD, Keiser PH, et al. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature 1998;396:690-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van de Velde RL, Friedman NB. Thymic myoid cells and myasthenia gravis. Am J Pathol 1970;59:347-68. [PubMed]

- Roxanis I, Micklem K, McConville J, et al. Thymic myoid cells and germinal center formation in myasthenia gravis; possible roles in pathogenesis. J Neuroimmunol 2002;125:185-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guptill JT, Sanders DB, Evoli A. Anti-MuSK antibody myasthenia gravis: clinical findings and response to treatment in two large cohorts. Muscle Nerve 2011;44:36-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corda D, Deiana GA, Mulargia M, et al. Familial autoimmune MuSK positive myasthenia gravis. J Neurol 2011;258:1559-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rieker RJ. Thymolipoma. In: WHO Classification of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. 4th ed. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, et al. editors. WHO Classification of Lyon: IARC;2015:289.

- Damadoglu E, Salturk C, Takir HB, et al. Mediastinal thymolipoma: an analysis of 10 cases. Respirology 2007;12:924-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rieker RJ, Schirmacher P, Schnabel PA, et al. Thymolipoma. A report of nine cases, with emphasis on its association with myasthenia gravis. Surg Today 2010;40:132-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moran CA, Rosado-de-Christenson M, Suster S. Thymolipoma: clinicopathologic review of 33 cases. Mod Pathol 1995;8:741-4. [PubMed]

- Reintgen D, Fetter BF, Roses A, et al. Thymolipoma in association with myasthenia gravis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1978;102:463-6. [PubMed]

- Otto HF, Loning T, Lachenmayer L, et al. Thymolipoma in association with myasthenia gravis. Cancer 1982;50:1623-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saux MC, Mosser J, Pontagnier H, et al. Pharmacokinetics of doxycycline polyphosphate after oral multiple dosing in humans. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 1982;7:123-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santos E, Coutinho E, Martins da Silva A, et al. Inflammatory myopathy associated with myasthenia gravis with and without thymic pathology: Report of four cases and literature review. Autoimmun Rev 2017;16:644-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Le Marc'hadour F, Pinel N, Pasquier B, et al. Thymolipoma in association with myasthenia gravis. Am J Surg Pathol 1991;15:802-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roche JC, Capablo JL, Ara JR. Myasthenia gravis in association with extrathymic neoplasia. Neurologia 2014;29:507-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rezania K, Soliven B, Baron J, et al. Myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune manifestation of lymphoma and lymphoproliferative disorders: case reports and review of literature. Leuk Lymphoma 2012;53:371-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mehmood QU, Shaktawat SS, Parikh O. Case of rhabdomyosarcoma presenting with myasthenia gravis. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:e653-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gattenlohner S, Marx A, Markfort B, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma lysis by T cells expressing a human autoantibody-based chimeric receptor targeting the fetal acetylcholine receptor. Cancer Res 2006;66:24-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hartert M, Strobel P, Dahm M, et al. A follicular dendritic cell sarcoma of the mediastinum with immature T cells and association with myasthenia gravis. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:742-5. [PubMed]

- Kim WY, Kim H, Jeon YK, et al. Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma with immature T-cell proliferation. Hum Pathol 2010;41:129-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

杨文圣

副主任医师,病理学硕士,中国人民解放军陆军第73集团军医院(暨厦门大学附属成功医院)病理科主任。从业十多年,具有丰富的业务经验,擅长消化、呼吸、神经、乳腺、纵隔、男女性泌尿生殖、皮肤、骨与软组织以及淋巴造血等系统疾病的临床病理诊断与鉴别诊断。先后参与国家级及省级自然科学基金资助课题5项,并主持厦门市科技计划项目2项。至目前已发表学术论文50多篇,其中以第一作者及通讯作者发表SCI论文3篇、中文核心期刊论著20多篇,参编专著《感染病理学》、《进展期胃癌的个体化诊疗》等,并荣获第14届福建省自然科学优秀学术论文三等奖等。当前学术任职:中国研究型医院学会超微与分子病理学专业委员会委员,中国医疗保健国际交流促进会病理学分会委员,福建省科技厅引导性项目评审专家,福建省医学会病理学分会委员,福建省抗癌协会肿瘤病理专业委员会委员,福建省医师协会病理科医师分会青年委员会委员,福建省海峡医药卫生交流协会临床肿瘤学诊疗分会介入微创学组、神经内分泌肿瘤学组常务委员,厦门市医学会病理学分会副主任委员,厦门市病理质量控制中心常务委员,厦门市思明区人民法院医疗咨询专家库成员等。(更新时间:2023/2/23)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)

Cite this article as: Marx A, Ströbel P, Weis CA. The pathology of the thymus in myasthenia gravis. Mediastinum 2018;2:66.