The evolution of thymic surgery through the years in art and history

Introduction

The origin of the name of the thymus gland is shrouded in mystery. The name thymus comes from the Latin derivation of the Greek thymos, meaning “warty excrescence,” due to its resemblance to the flowers of the thyme plant. The homonym thymos translates as soul or spirit, and it is for this reason that the thymus was misrepresented as the seat of the soul by the ancient Greek anatomists presumably in reference to the intimate anatomic relation between the thymus and the heart (1-3).

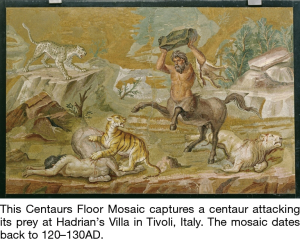

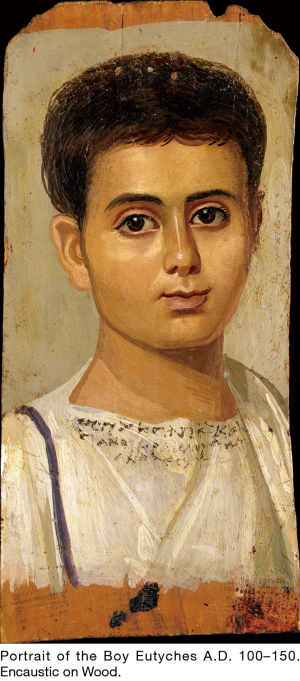

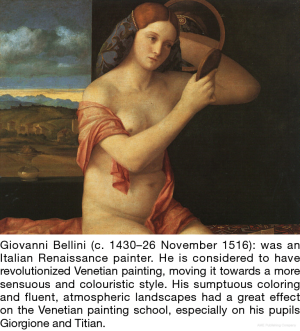

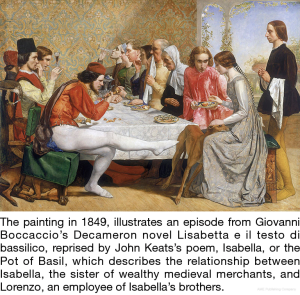

Early history (Figures 1-7)

The earliest known reference to the thymus is attributed to Rufus of Ephesus circa 100 AD (3). A Greek anatomist renowned for his investigations of the heart and eye, Rufus attributed the discovery of the thymus to the Egyptians. Rufus quote “There are many glands, some of which are in the neck, others in the groins, others in the mesenteric ganglion, try are a sort of friable flesh. Amongst these glands there is on call the thymus situated under the head of the heart, oriented towards the seventh vertebra of the neck and towards the end of the trachea’s that touches the lung.

The most famous physician of antiquity, Galen of Pergamum (130–200 AD), stated that the thymus played a role in the purification of the nervous system, was also the first to note that the thymus was proportionally largest during infancy (4). He was the initiator of the experimental, methods applied to the study of anatomy and pathology and stated that “the inferior wall of the vena cava rests on a quite soft and bulky gland called thymus, and is far from being small, instead large, most especially in young animals, and gradually dwindles with growth”.

Thymus was re-described by Italian anatomist Giacomo Di Capri 1470–1550. He was a lecturer of anatomy and surgery at the University of Bologna (3).

William Hewson published the first scientific dissertation on the thymus. On the basis of findings of his investigations in dogs and calves, Hewson described the evolution of thymic size during fetal and infant life, thus verifying Galen’s observation. He concluded that the thymus itself was some sort of modified lymph gland (5). He stated “The thymus gland we consider an appendage to the lymphatic glands… expeditiously forming the central particles of the blood of the fetus”, and found that the thymus was larger in the old than the young. Hewson was father of hematology gave initial clues of the function, but for some time theories of the thymus led by famous greats including Virchow as a source of pediatric death due to thymic asthma or status thymolymphaticus.

First surgery [1896] Ludwig Rehn [1849–1930] Transcervical Thymopexy Partial Thymectomy for respiratory distress. Followed by Henry Pancoast who used fluoroscopy and significant exposure to radiation to find enlarged thymus. This was closely flowed by followed by Alfred Friedlander in 1907 who formally treated a child with dyspnea with X-ray radiation, thousands of infants and adolescents were then irradiated, that later let to thyroid and breast cancer, until 1945 when this was discredited.

1900–the present day (Figures 8-22)

Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch (1875–1951) in 1911 performed the first transcervical total thymectomy for thyrotoxicosis in a 19-year-old adult female with myasthenia gravis (MG).

The treatment of thymic Asthma, from “1910–1924 was reported by Vea Veau. “C’etait l’age d’or de la chirurgie thymique” (I) thymopexy, (II) manubrectomy, (III) thymectomy. For the treatment of asthma it was the golden age of thymic surgery, debunked in 1931 by Turnbull Commission. The British investigators Greenwood and Woods characterize status lymphaticus as “this heap of rubbish,” stating furthermore that “the present use in certification and in evidence in coroners’ courts of the phrase Status Lymphaticus and Status Thymic Lymphaticus is... a good example of the growth of medical mythology (6). A nucleus of truth is buried beneath a pile of intellectual rubbish, conjecture, bad observations, rash generalization.” The British commission headed by Young and Turnbull was unable to locate in status lymphaticus even a “nucleus of truth” and concluded that no such condition exists (7). A lesson in history we should all head.

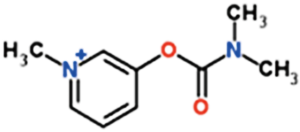

The true golden age of the study and understanding of MG began with the understanding of a central cause, the acetylcholine antibody, and as well with the discovery of Pyridostigmine to obviate the effects of the antibody.

The first case of MG was described in 1672. Treatment of MG was negligible until Mary Walker’s seminal observation in 1934 of improvement with physostigmine and neostigmine injections. Blalock reported the initial success with thymectomy around 1940. Edrophonium was introduced around 1950 and pyridostigmine in the mid-1950s. John Simpson’s hypothesis of an autoimmune etiology for MG in 1960 was later proven correct, and subsequent use of immunosuppressive therapy including corticosteroids led to the modern era in management of MG.

Alfred Blalock (1899–1964) performs first thymectomy by partial sternotomy for tumor (with MG) in 1936 (8) and in 1941 published his landmark series of planned thymectomy for non-thymomatous MG in Journal of American Medical Acadamy (JAMA) (9).

In 1946 Keynes in the British Journal of Surgery reported on a large series of thymectomies for MG. He noted the invariable presence of large thymic vein draining into left innominate, close union of thymus and pleura and the Extension of thymus over pericardium. And writes, that it “demonstrates the folly and danger of attempting to remove the thymus from the suprasternal incision” (10). He goes on to describe and illustrate a partial sternotomy for thymectomy.

Subsequently, in 1969 Kirshner/Osserman reported 21 patients undergoing trans-cervical resection for MG (11). He cites a brief, bland, postoperative course and simplified management of myasthenia by avoiding a large, painful, chest-splinting sternotomy incision. Contraindications include large, inaccessible thymomas and low-lying preexisting tracheostomy. At the end of one year, 3 patients had borderline remission, 6 showed improvement and three showed no change. Eight patients were operated on too recently to evaluate. There was 1 postoperative death. He reports “Trans-cervical total thymectomy is now our surgical procedure of choice in myasthenia gravis” (11).

In 1975 Professor Akira Masaoka documents extra-thymic rests of thymic tissue in the mediastinum, which led to the establishment of the trans-sternal extended thymectomy approach as a treatment option for MG (12). Of course, another significant accomplishment was in 1981 the proposal of a clinicopathologic staging system for thymic tumors that depends on local tumor invasion and distant spread to the pleura, lymph nodes and distant organs. This staging system was globally adopted and remained the standard for over 30 years (13).

Surgical innovations

Puglionisi et al. in 1978 describe a case of malignant neoplasm of the mediastinum affecting the S.V.C. and the right lung. Radical removal of the neoplasm involved a right pneumonectomy and resection of the S.V.C. Replacement of the latter with a prosthesis in Dacron double velour was successful—which has lasted 5 months to date (14). And In 1987 Dartevelle et al. published their case series: Replacement of the superior vena cava with polytetrafluoroethylene grafts combined with resection of mediastinal-pulmonary malignant tumors. Report of thirteen cases that helps usher in the ability to completely resect stage 4 thymic neoplasms (15).

Cooper et al. used the transcervical method of thymectomy in patients with MG, with important technical innovations, and believed that complete thymectomy be accomplished with minimum morbidity. They used an improved technique for the trans-cervical approach, employing a specially designed sternal retractor that permits improved visualization of the anterior mediastinum. Results from 65 patients operated on between 1977 and 1986 were reviewed. Comparing these results with those reported following thymectomy through a sternotomy reveals that the trans-cervical approach can yield equivalent results (16). In what would prove to be great academic rivalry, Jaretzki reported his maximal thymectomy surgical treatment of MG. In this report he describes an operation that predictably achieves that goal in most patients. “The results of surgical-anatomic studies in 50 consecutive specimens obtained by this technique indicate that an en bloc transcervical-transsternal “maximal” thymectomy is required to ensure removal of all available thymus in all patients. This procedure is recommended for all patients undergoing thymectomy in the treatment of MG with or without thymoma and in the treatment of thymoma with or without MG (17). Although both presented radically different approaches, both surgeons did in fact passionately support the need for and importance of a complete resection of thymic and perithymic tissue containing remnants of thymic tissue.

Presently the debate in regards to the effectiveness of thymectomy for MG in non-thymomatous MG was settled with the results of the MGTX trial (18). Many minimally invasive techniques have now been described to reliably remove as much thymic tissue as possible, and to effectively and safely remove thymic neoplasms, the tenets of our surgical heritage remain important guides to our continued evolution.

Acknowledgments

This work is made possible with Generous support of the Price Family Center for Comprehensive Chest Care.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors Mirella Marino and Brett W. Carter for the series “Dedicated to the 8th International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group Annual Meeting (ITMIG 2017)” published in Mediastinum. The article has undergone external peer review.

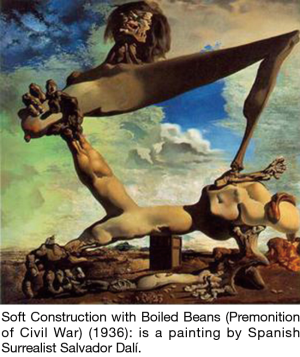

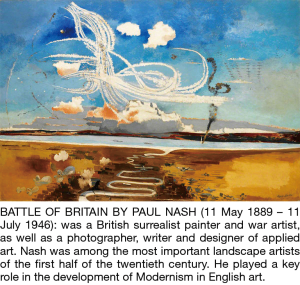

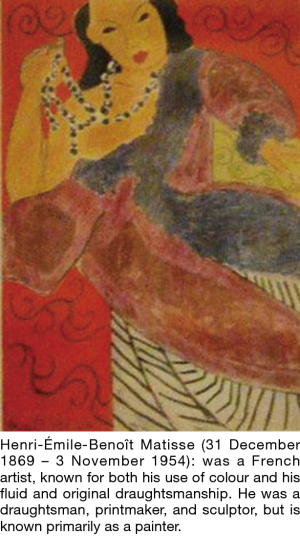

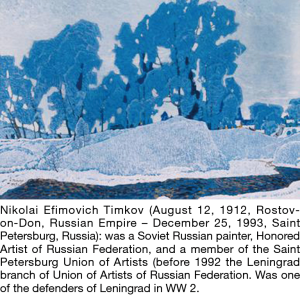

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/med.2018.03.20). The series “Dedicated to the 8th International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group Annual Meeting (ITMIG 2017)” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. This study has been presented at 8th International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group Annual Meeting (ITMIG 2017). All the figures are from public access like WikiArt, Wikipedia, etc.; they are of fair use or in the public domain. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Silverman FN. A la recherché du temps perdu and the thymus (with apologies to Marcel Proust). Radiology 1993;186:310-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haubrich WS. Medical meanings. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians, 1997:225.

- Lavini C. The Thymus from Antiquity to the Present Day: the History of a Mysterious Gland. In: Lavini C, Moran CA, Morandi U, et al. editors. Thymus Gland Pathology. Milano: Springer, 2008.

- Singer CS. Galen on anatomical procedures. London, England: Oxford University Press, 1956:250.

- Hewson W. Experimental enquires III. In: Cadell T. editor. Experimental enquires in to the properties of the blood. London, England, 1777:1-223.

- . Greenwood, Woods HM. "Status Thymico-Lymphaticus" considered in the light of Recent Work on the Thymus. J Hyg (Lond) 1927;26:305-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Young M, Turnbull HM. An analysis of the data collected by the status lymphaticus investigation committee. J Pathol 1931;34:213-58. [Crossref]

- Blalock A, Mason MF, Morgan HJ, et al. Myasthenia gravis and tumors of the thymic region. Ann Surg 1939;110:544-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blalock A, Harvey AM, Ford FR, et al. The Treatment of Myasthenia Gravis by Removal of the Thymus Gland preliminary Report. JAMA 1941;117:1529-33. [Crossref]

- Keynes G. The surgery of the thymus gland. Br J Surg 1946;33:201-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kirschner PA, Osserman KE, Kark AE. Studies in Myasthenia GravisTranscervical Total Thymectomy. JAMA 1969;209:906-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masaoka A, Yamakawa Y, Niwa H, et al. Thymectomy and malignancy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1994;8:251-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masaoka A, Monden Y, Nakahara K, et al. Follow-up study of thymomas with special reference to their clinical stages. Cancer 1981;48:2485-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Puglionisi A, Picciocchi A, Cina G, et al. Prosthetic replacement of the superior vena cava after resection for malignant mediastinal tumour. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1978;19:627-32. [PubMed]

- Dartevelle P, Chapelier A, Navajas M, et al. Replacement of the superior vena cava with polytetrafluoroethylene grafts combined with resection of mediastinal-pulmonary malignant tumors. Report of thirteen cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1987;94:361-6. [PubMed]

- Cooper JD, Al-Jilaihawa AN, Pearson FG, et al. An improved technique to facilitate transcervical thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Thorac Surg 1988;45:242-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jaretzki A 3rd, Wolff M. "Maximal" thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Surgical anatomy and operative technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1988;96:711-6. [PubMed]

- Wolfe GI, Kaminski HJ, Aban IB, et al. Randomized Trial of Thymectomy in Myasthenia Gravis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:511-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Singh G, Sonett JR. The evolution of thymic surgery through the years in art and history. Mediastinum 2018;2:33.